5. Into the North

© 2017 Daniel YordyFebruary 1977 - June 1977

Unexpected Patterns

Setting forth an account of my life has become something I did not expect. I did expect healing, and I did intend to call every moment by Christ, regardless. What I did not expect was to see the array of patterns opening up that demonstrate God’s intentions towards me all the way through.

I hope, now, to show you those remarkable patterns of God in my life and what they meant. But I do not want you to think of me as anything other than a normal man somehow caught in the grip of Someone way bigger than me. I set this account of my life before you as an example that you also come out from your Father through the good speaking of Jesus and that, as you call every moment of your life by Christ as well, so you will see that God was always involved in your life just as much. “Superior saintliness” is not the mark of the Father; the mark of the Father is being carried through every stumbling step.

Always before I have looked at my failures as the defining points of my life. Now, it dawns on me that my many failures were just the background hum, the backdrop, so to speak. The defining points of my life were those specific moments either when God contended with me Forehead to forehead or when He planted a particular Word as a Seed in my heart, seeds that would lie hidden in my ground for years until they seemed to spring forth in full fruit as if they were the only things real.

This time period, from February of 1977 until May of 1979, is the foundation of my present knowledge of God. I have referred to it many times as a time of entering into a covenant with my Father. That final moment of that experience, in May of 1979, I have called “Cutting the Covenant.” Indeed, Genesis 15 is apt, the “deep sleep,” the cutting apart, the blood on the hillside, a God of fire passing through my split-open soul.

Yet I was just a boy of twenty to twenty-two experiencing life’s joys and sorrows, fun times, good things, new experiences, and endless foolish mistakes and embarrassments.

The dissolving of my friendship with Andy opened a deep emptiness in me. But to understand my agony through February and March of 1977, I must share something about myself that I have only recently realized.

I experience, on a regular basis from my childhood until now, great depths of emotion that I have called an “angst,” a wordless cry, a reaching towards something I cannot see, but that I know MUST BE. I’m not speaking of something small or occasional, but of a huge internal agony that is often. Until recently, I had thought of this as nothing more than “weird me.” Or, at least for the last several years, as part of being Asperger’s.

I now understand this quality as the pressures of “travail,” the inexpressible groanings of the travailing Holy Spirit inside of whom we live. I used to call it awfulness or angst or “what is wrong with me?” Now, as I call my whole life to be one seamless story of Christ, regardless, I realize that from childhood, I have been seized in God’s grip through every circumstance. When I look back now, calling everything in my life by Jesus, I see two things concerning this agony of travail that marked my person since I was nine. First, it was a quality of spirit, a reaching forward into something I knew must be there, but did not know at all. And second, it was a deep anguish to see and to know something real, life as it was meant to be.

Now, I am presenting myself as nothing more than a normal part of God’s creation. Here is the reality of all. – The entire creation groans together and travails together until now. Not only that, but even we ourselves, possessing the firstfruit of the Spirit, we also groan inside ourselves, eagerly expecting… (Romans 8:22-23). Your entire life has been the same travail. See it as so, call it to be so, every moment. Call every moment of your life by the hand of God and not by any purposeless confusion.

February and March of 1977 were filled with this agony, far more than “normal,” but in confusion and with no real understanding of God.

An Experience inside the Agony

In early February, Pastor Bob Adams read a letter to the Skyline Assembly, written by Jim Buerge and addressed to the congregation, who had known him well through his time as an elder in that church. In this letter, Jim shared about the work in which he and his family were involved, ministering to the First Nations people in the mountains above Ingenika at the north end of Lake Williston in northern British Columbia. They were living at a trapline in a place called “Eagle Rock.” Everything he shared intrigued me – ministering to the “Indians,” and living with others in the remote mountains of the North.

British Columbia – the North – had always intrigued me similar to looking up the logging road had intrigued me when I was a boy. Every mention of northern “wilderness” excited me.

Sometime in 1976, we had heard a terrible report of great loss. In order to get from Ingenika up to Eagle Rock, the Buerge's had to cross a mountain river on a raft. This was normal and reasonably safe. But that summer, as Jim and his wife, Jean, and their five children, accompanied by another brother by the name of John Clarke, going with them to minister to those at Eagle Rock, were making this normal crossing. The water was a bit high and rough and, for some reason, the raft was caught in the flood, and they were all tipped into the torrent. Jim’s wife and their two youngest children did not make it to the shore, but were drowned.

Since all of us at Skyline knew of this tragedy, we gave ear to the things Jim shared.

Not long after the reading of this letter was Skyline Assembly’s yearly “winter camp.” Everyone in the church who wanted to participate went up to a lodge just off of Highway 20 in the high Cascades. I had been to many camps as a boy, but this time was different, this time it was the whole church, men, women, and children, with me as part of that church.

The lodge was large. The men slept in bunkrooms on one side and the women slept in bunkrooms on the other. The large room between was commodious, with around 50 people there. The snow outside was deep and the slopes were perfect for every kind of sledding and tubing. We were there Friday evening through Sunday. We ate our meals together, we played together in the snow and sliding down the long hillsides. I had the chance to ride a snowmobile. I remember a prolonged game of chess with a brother from the church. We worshipped and shared communion together.

I drove home by myself that Sunday afternoon, weeping the entire way. “That was so right; that was so right,” I told myself over and over, “that’s what church is meant to be.” I had never heard of Christian community, and I had no idea how this longing for life as it is meant to be could ever be fulfilled. Nonetheless, on that trip down the mountains out of the snow and into the wet valley below, I conceived the idea that maybe, just maybe, I could go up north to where Jim Buerge and his family lived at Eagle Rock. Maybe sharing time with them would begin to answer that deep longing for REAL.

You see, Jim had also shared in the letter that he and his remaining children were coming down to Oregon at the end of March and would visit Skyline Assembly.

One more thing that added to these two months of agony was the fact that I had recently read Rees Howells: Intercessor by Norman Grubb. The primary things I gained from reading this account of Rees Howells' life was first that a man could know and walk with God in close fellowship and second, that God is well able to do what He says in our lives. I see now that this was an increase of that which I had gained from reading Madame Guyon.

So here I was, caught through these two months, between emptiness and loss of friendship, confusion and disconnect on the one hand and a deep cry inside calling me towards something I did NOT know anything about. I was split apart, and I could find no answers.

Visitors at Skyline

The Buerge’s came in late March, Jim, with his daughter, Pamela, and his two sons, Tony and Tim; Jim shared a greeting and testimony with the Skyline Assembly church. That Sunday afternoon, I went to visit with Jim at his mother’s house in north Albany. I shared with him my desire to spend time with them in northern British Columbia.

“It may not be possible for you to come right out where we are,” he said. “But my brother Del and my sister Rhonda and their families are living in a community called Graham River Farm. That is where we lived before we moved out to Eagle Rock (the trap line in the Rockies). I would suggest you spend some time there and get to know what we are about before you consider coming out to Eagle Rock. Graham River Farm covers us, and they have a say as well in who comes out to be with us.”

Jim was a bit hesitant in sharing this. You see, standing before him was a 20-year-old boy with long stringy hair down to his belly and with a scrubby goatee on his face. Outwardly, I did not look like a “candidate” for the fellowship and way of life he knew was the experience of community at Graham River Farm.

As he suggested that I go to Graham River first, however, I felt a peace flow into my heart that it was the Lord. “Yes, I would like to go there,” I said. He suggested also that I might want to cut my hair and shave first. For the first time, I was willing to do that – and did. That fact alone probably assured him that I was at least serious.

Jim and his children had driven down in his little Scout. He was in Oregon to close out some business endeavors he had been involved in and to buy a plane to take back north. He asked if I would drive the Scout back up to Graham River Farm while he and his children flew in the plane. I was quite willing. Thus, in early April of 1977, I headed north into what was for me the uncharted wilderness of northern British Columbia. I was twenty years old; and I love adventure.

Graham River had such an impact on me that I am taking more pages to cover these next two years than I have thus far.

The Trip Up

Jim Buerge asked me to take a cage full of pigeons up to his brother, Del. Jim had called the border and had fulfilled all the requirements they told him in order to take the pigeons across. However, when I arrived at the crossing at Sumas, Washington on a Friday evening in early April 1977, I learned that a Canadian vet would have to inspect the pigeons before they would be allowed to cross. The Canadian vet would not be available until Monday morning. So I turned around to go back, only now the American customs baulked at my bringing the pigeons into the States. So there I was caught in the no-man’s land between two countries. The Americans soon believed my story and allowed me to proceed. I spent the weekend in a motel in Sumas.

On Monday morning, Jim flew up with his children, Pamela, Tony, and Tim. He took charge of the pigeons, so I did not have to worry about that part. However, when I went to the counter to ask for a visa, I made a mistake. I asked a question. I have never asked a question when crossing a border since. I asked, “What do I need to do to obtain a work permit in Canada?”

“Work?” the lady asked. “Work? You will not work in Canada!” At that point she was unwilling to let me through. Jim came in and talked with her; finally she was persuaded to give me a three-week visa on strict conditions. I had to post a $100 bond and lose the money if I was not out of Canada in three weeks. I had hoped to spend three months, so this was a disappointment to me at the time. She also said, “You can make your bed, but you cannot help wash the dishes or anything else. You may not work in Canada.” I since learned that the border officials take a narrower view of things than do the immigration officers who supervise visitors in the interior. I was free to proceed north.

I drove up through the Fraser River canyon and across the Cariboo country to Prince George. This was the first time across a road I would travel dozens of times in the future. We spent the night at some friends of the Buerge’s in Prince George, and the next day, Jim had Tony ride with me the rest of the way. We crossed the Pine pass and descended into the Peace River country. I was amazed to see solid grain farming country with tall silos this far to the north. It was the end of winter. There was still snow on the ground, though it was disappearing, and there were not yet leaves on the trees. It was the season of mud.

We drove north on the Alaska Highway from Fort St. John. Soon most signs of civilization disappeared. The pavement ended at Mile 93. At Mile 95 we turned west from the highway onto a primitive gravel road. We wound up and down for forty miles into the foothills of the Rockies. There was a bridge across the Halfway River, but none across the Graham. We came to a stop on the banks of the Graham River. I caught glimpses of log cabins on the other side. There were a number of vehicles parked on this side and a dirt road running down to the water. The ice was mostly gone, but the river was not yet high from the spring melt in the mountains. We honked the horn and waited; it was late afternoon. The spruce trees were green and dark, the poplar trees still leafless. The Graham River was a fairly large river, strong and full. This was an utterly new experience for me. Adventure beckoned, calling to the cry of my heart.

Adventure

After a short wait, we heard a tractor coming through the trees on the other side of the river. It soon appeared and plunged right into the water, pulling a long wooden hay wagon behind it. The water came up only to the tractor axles. The gravel bottom of the river had been smoothed to make a good ford. We put our things on the hay wagon and stood up, holding onto the rail in the front. There were no side-walls to the trailer. We bounced across the river, wound through some trees on the other side, and then up a short embankment. Graham River Farm opened before us.

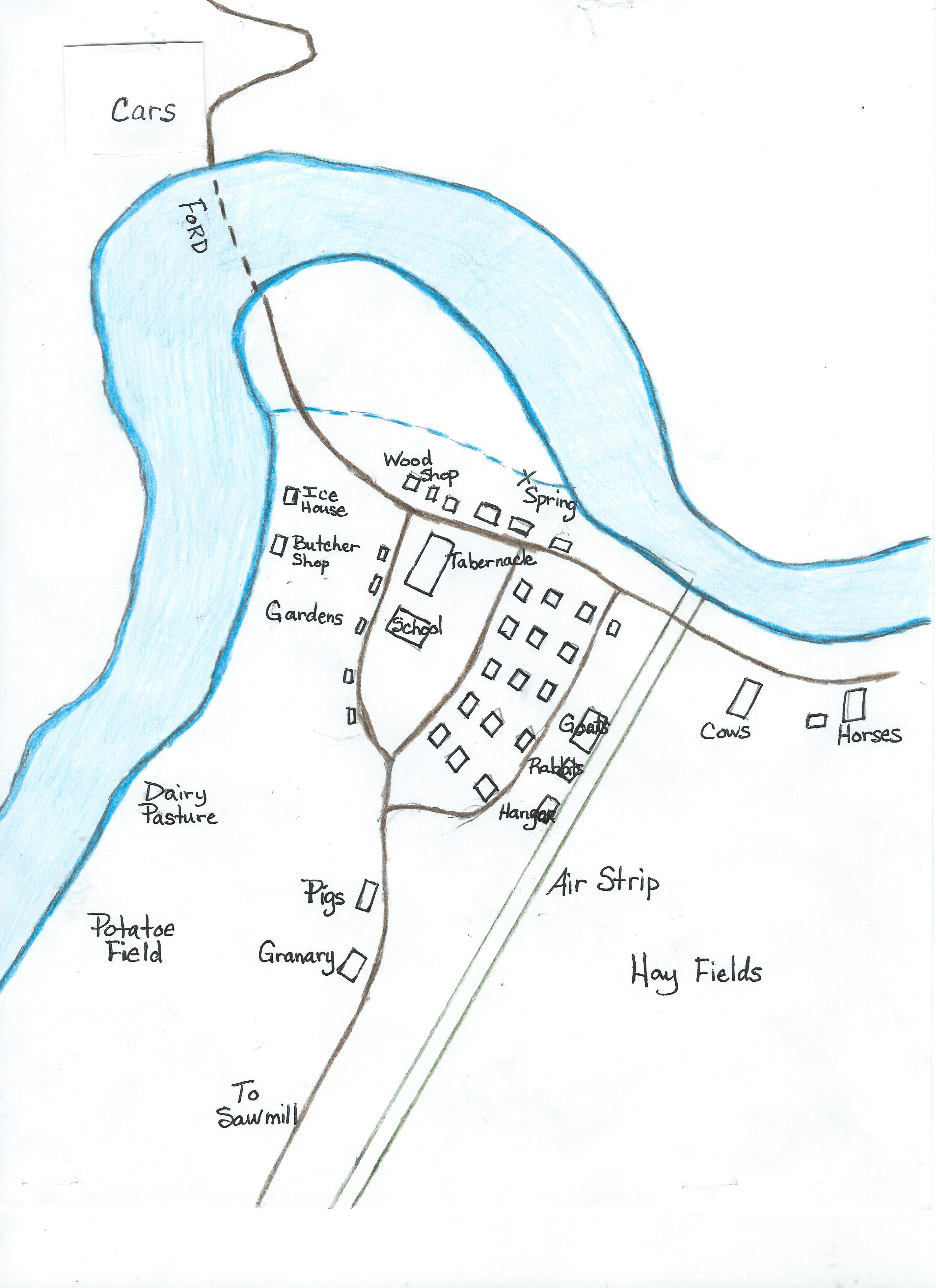

The community was like nothing I had ever seen before. All of the buildings were made of logs, roughly hewn together. On our left was a mechanics shop, to our right was a long, low building I would soon learn was called the Tabernacle. Just beyond it was a newly completed two-and-a-half-story building, the schoolhouse. On the nearer side of the Tabernacle was a row of small log cabins stringing out into the distance. This row was on the edge of an embankment overlooking muddy and partly snow-covered fields that would become the gardens during the summer months. Beyond the Tabernacle were three more rows of cabins, and beyond them, in the distance, I could see some large barns. The cabins themselves were unique. They were small, most about 20’ x 20 or 25’, all only one story with a low lean-to roof. They looked like rows of chicken coops, around twenty-five in all.

We stepped through a rough-hewn door into the Tabernacle. I looked out across a dining room with a low wood ceiling and log walls. The room was probably about 30’ wide by 70’ long. There was a large wood stove not far from this entrance, and the room was filled with rough wood tables with backless benches on each side. On the right was the counter dividing the kitchen. I had never seen anything like it before.

Someone took me to a cabin whose occupants were away. I would be staying here for a few days. The cabin was low and dark. After a bit I heard a bell ringing; it was time for supper. This time the Tabernacle was filled with people! One hundred and fifty people sat down around those rough tables to share their supper meal together. What a sight! There were large numbers of children, adults of all ages, families and singles. They talked and laughed happily, joy and peace shining on all the faces. I was enthralled. We shared a simple meal together. I don’t remember what it was, but I’m sure it was potatoes. I have eaten a lot of potatoes. I was greeted pleasantly, but no one made a big deal out of my being there.

There was no electricity except a generator in the welding shop. The Tabernacle had propane lights, and many of the cabins had one propane light in them. Otherwise kerosene lamps were used. I slept that night in a cabin by myself. The next morning after a hearty bowl of cracked grain for breakfast at the Tabernacle, I went to the work circle where the men received their assignments for the day. I don’t remember what my first detail was, probably firewood, but I went to work. I began to meet the people. I had known Del Buerge and his family in Oregon, and had greeted them the evening before, but I did not know them well. All the rest of the people were complete strangers to me. It would take a long time to put together names, faces, and cabins.

For the next few days I went to the meals, worked with other men on whatever assignment I was given, and slept by myself in my cabin. No one invited me over to visit; no one talked with me about what this place was all about. I felt a bit lonely. Finally, after several days, I was moved to a cabin belonging to Bill and Dot Ritchie and their son Rohn. They were away from the farm, but a single young man named Harleigh Knapp was also staying there. He had a bed in the entry and I took Rohn’s bed. I now had someone to talk with, although Harleigh was not the most talkative person and neither was I.

One job I did was to work with Tabor Mercier, a husky big-hearted man, on the firewood sawing detail. He had a large saw blade mounted on the front of a tractor. The blade had a platform in front of it. Tabor hoisted short lengths of log up onto the platform and swung it into the blade to make stove-sized pieces of wood. The members of his crew, including myself, handed the lengths of wood up to him, helping him get them on the platform, and then caught and stacked the firewood as it was cut. Another job I did was to go with Doug Witmer and Mallory Smith, young men my age, down to the grain bin. There we hooked a belt up between a tractor and a hammer mill, a device for grinding grain. The size of the screen would determine whether we produced flour for bread or cracked grain for breakfast cereal. My job was to fill and lug buckets of grain from the grain bins to the hammer mill and to help tie the sacks and stack them when they were full. All of it was good, hard, basic-to-life sort of work.

Contending with the Word

The community had two services a week, besides the morning devotions. There was a sharing service on Wednesday night during which any member of the community could go up and share. The main service was on Saturday night during which only the elders preached. The praise services were long, strong, and anointed. I could sense the presence of God like I had never known. I did not understand most of what I heard. And the few things I did hear, I thought were really weird. One girl stood up and shared that she was learning that her life was really in her brothers and sisters. I thought “No way, my life is in Christ.” I had forgotten that Christ was also in the people around me. Another brother shared that we needed to walk out the righteousness of Christ. I thought, “Baloney, Jesus is my righteousness, not what I do.”

Harleigh suggested I attend a Bible study one evening at Ian and Isabelle Still’s cabin. Ian and Isabelle were from Scotland and had immigrated to Canada specifically to live at Graham River Farm. I soon learned that most of the other people at Graham River were from the states: from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New England, and had also immigrated to Canada to live at Graham River. Ian and Isabelle were a lively, good-hearted couple who spoke with a strong Scottish accent and laughed a lot. They were also very serious about the word and the truth God was speaking. They were unusual in the community in that they had only one child, a son, Gavin. Most of the families had five, six, seven children each. We were studying the book of Revelation. Isabelle said “Wasn’t it so silly when we used to think that heaven had literal streets of gold?” I thought, “What are you talking about, of course heaven has streets paved with gold.” She went on to say that the golden streets in John’s vision meant that when we come to the fullness of all God has for us, we will be walking in the very nature of God, of which gold is a symbol. I had never heard of such a thing.

Somebody gave me some tapes by a man named Sam Fife. I had never heard of Sam Fife, but I took the tapes to the cabin and began to listen. It was only a few minutes before I slammed the tape recorder off and said loudly, “Baloney, this stuff is nonsense.” Harleigh looked at me quietly, and said, “We can only walk in the light God gives us.” I did not know what he was talking about. There was a problem for me, though. Sam Fife was the first preacher I had ever heard who spoke with the authority of the Holy Spirit. Something inside me was drawn to the anointing in which he was speaking. I spent a number of evenings alternately listening, and then slamming the tape recorder off and fuming.

From the very first moment that I slammed the “off” button on the tape recorder the very first time I heard Sam Fife speaking on a tape, I became deeply, deeply distressed about the Word God speaks. – What does God actually say in the Bible? This was an autistic agony of immeasurable proportions. Up until that moment, I had studied the Bible because I wanted to learn of God and of the power and meaning of the Christian life.

From that moment on, I KNEW that someone was misrepresenting what God says in the Bible. Of course, I knew that “someone” had to be Sam Fife. And so I opened my Bible to prove him wrong. I was 20 years old when this deep distress, this overwhelming desperation to know what God actually says in His word to me, began.

Finally, I worked one day with a crew of men cleaning the manure out of the pig barn. One of the men was Dan Kurtz, one of the elders. During a break, aside from the others, he asked me, “Daniel, where is Christ?” I hesitated and did not answer. He reached out a rough, tender finger and pointed it at me. “He is in you!” he said quietly. I knew from what the Lord had shown me the year before that it was true. Christ lived in me! That was the first word of this new strange-sounding teaching I was able to receive.

I was at Graham River for about two and a half weeks. I had to return to the states by Greyhound bus. I was glad at that point that I was allowed to stay in Canada for only three weeks. I was overwhelmed with the strangeness of it all, and I had much to think about and hash through in my own heart. I did not understand most of what I had heard and did not think it was true. I did not know why God had brought me there. I had the naive idea that maybe these people were in bondage and God wanted me to help them understand the “truth,” as if I knew what the “truth” was.

Before I had left Oregon to go to Graham River, Pastor Bob Adams of Skyline Assembly had taken me aside to share his “concerns” about this group I was going to visit. He had been there for a short visit. “They believe there are three groups or levels in the church, and they are the top one of the three,” he said. “Be very careful.” I had no idea what he was talking about, but I had heard something about this concept at Graham River. It was now one of the many questions I had.

Yet prior to Jim’s visit to Skyline, in response to things Pastor Bob knew were taught in the move fellowship, he had asked the congregation, “How many of you believe that a Christian can walk without sin,” he asked. I was sitting in the back of the church that Sunday. I must always answer honestly, as far as I am able. I thought to myself, out from my reading of Rees Howells, “With God all things are possible.” I raised my hand. All but one other did not.

This great contention now had me in its grip.

Dead-Ends

Upon returning to Oregon, I did not return to working with Jimmy and Andy. I did not want to go back to whatever hassles were inside of broken friendships. I tried two other jobs, but both ended quickly. I quit one, picking up branches in the National Forest for the forest service, because it was meaningless to me. I was fired from the other, a different construction crew, because I wore myself out and then called in sick. It seemed every direction was a dead-end.

Meanwhile, I searched my Bible. I had heard a number of things that had shaken my “Christian” beliefs to the core. I had to know what the Bible really said. Every spare moment I was not working, I was in the Word, searching and seeking to understand or to refute. I noticed something unusual. From the beginning of the Bible to the end, there were three divisions or levels of things: three feasts held by the nation of Israel, three parts of the tabernacle, three levels of fruitfulness - 30 fold, 60 fold, and 100 fold, and so on. I began to realize that three levels of knowing God was a Biblical concept. God was speaking something important.

I had no problem with the teaching I had heard about overcoming sin. I believed what Jesus said, “With man it is impossible, but not with God; with God all things are possible.” Certainly, God can do whatever He wants to do in our lives.

I now know that it is only too normal for Christians, receiving a deeper understanding of God, to see themselves as “superior” and to become sectarian. But this is a problem for all Christians. The word which the brethren at Graham River had received was breaking free from some of the serpent’s definitions common to all Nicene Christianity, some but not all.

Yet I have never seen a people who were so dedicated to a vision, or so willing to sacrifice everything valuable in this life to be a part of the kingdom of God, or so anointed in the power of the Holy Spirit. Whatever mistakes may have been made at Graham River or any other community I have been privileged to be a part of since, those mistakes were made out of misguided sincerity or personal weakness, never out of a lack of commitment to the Lord Jesus Christ.

There I was again in a dead-end place back in Oregon. I could see the Bible more clearly than I had before. I knew something was there beyond my acquired definitions of Christianity. I was simply waiting on God for the next step.

Then, one day in early June, I walked into a store in Albany, and whom should I meet but Jim Buerge! He had flown down again by himself to wrap up some business he had been unable to complete earlier. “Hey,” I thought, “maybe I can go back to Graham River!” And so I did.

The Return Trip

Jim Buerge knew a family from Salem who were moving to a small community near Edmonton, Alberta that was associated with Graham River Farm. He suggested that I ask about traveling up with them. Once in Edmonton, I might be able to get a ride up to Fort St. John. This family, the Widmer’s, agreed that I could ride with them.

We crossed the border at the crossing in northern Idaho. There my experience was opposite the first time. A kindly gentleman gave me a three-month visa to Canada with no problems. I would be able to get an extension through the immigration official in Dawson Creek, the town at the beginning of the Alaska Highway. We drove on to the town of St. Albert just north of Edmonton. Just beyond the outskirts of the city there was a small farm purchased by Christians who had established a small community there. Besides the main house there was a bunkhouse where I stayed with two other fellows, Patrick Downs and Rustin Myers. Patrick had just emigrated up from Houston, Texas and was working in Edmonton for a season before going on to a newly started community called Hilltop, also north of Fort St. John. I enjoyed a couple of days with them.

Then a couple of gentlemen came down from another Christian community called Shiloh that was not far from Graham River by a straight line, although by road it would be 80 miles. Their names were Don Deardorff and Fred Vanderhoof. They had come down to Edmonton in a truck to pick up a load of windows. They agreed to take me with them on their return trip. I found them to be hilarious. Don was short and skinny and Fred was tall and skinny. They told jokes and laughed all the way back to Fort St. John. Don Deardorff’s laugh is quite infectious. Years later, at the Blueberry community, his table often erupted into gales of laughter during the meal, enough to cause heads to turn to see what was so funny. His children laugh the same way.

It was a pleasant trip for me from Edmonton to Fort St. John. It was June and full summer now. The whole Peace River country was considerably different than when I had seen it two months earlier. The north has four seasons, white, mud, green, and mud, and then white again. The white lasts the longest, six months, the green lasts only three months. The mud season is between them on both ends. Now it was green and breathtakingly beautiful.

Upon our arrival in Fort St. John, Don and Fred dropped me off at the home of a family, the Burnham’s, who were associated with the communities and who made their house available to anyone coming into town from the farms needing a place to stay. I did not realize it at the time, but as I entered Fort St. John, that June of 1977, the Lord was turning my life into a different phase of experience with Him. It was a time of judgment. I was a mess inside and completely closed up, though I did not know it. Somehow God had to pry my shell apart so that He could eventually heal and restore. I was entering a furnace, a glorious furnace of affliction.

I spent two days at the Burnham’s until the town trip from Graham River came to town. It was a van full of folks come to do their shopping. Many often came into town only once a month, though there was a town trip once a week. I had to wait all day until they were ready to return. It was late by the time we left Fort St. John, with a two-hour trip ahead of us. We were just a few miles from the turnoff to the Graham River when our tire blew. The driver, Todd Booth, did not have all that he needed to fix it, so he had to walk the few miles to get help. It was around three in the morning before we finally made it across the river and onto Graham River Farm. The delay must have been the Lord because right around the time we would have arrived, a bear was prowling around right at the Tabernacle. He tried to get into the cheese house, leaving marks on the window with his face. Then he meandered over to the butcher shop nearby, trying to get in there. He succeeded at that, only not the way he intended. One of the brothers shot him next day; they turned him into food for the table.

Origins of the Communities

There were several community farms in the Peace River region. Graham River, Shiloh, and Headwaters were all to the west of the Alaska Highway and north of Fort St. John, in the foothills of the Rockies. Blueberry, Evergreen, and Hilltop were to the east of the Alaska Highway and a little closer to Fort St. John. Finally, Peace River Farm was only a few miles west of Fort St. John in the canyon of the Peace river, and Hidden Valley was southwest of Dawson Creek, the furthest from the others. Peace River farm had just been bought out by the government in preparation for a dam that was never built. Some of the people from that community went on to other communities and some called it quits.

Most of the people in the communities had emigrated from the states specifically to establish these communities on the edge of the wilderness, a number also coming from eastern Canada. Graham River was the first to begin, in the early summer of 1972, with Headwaters and Shiloh starting later that summer. Hidden Valley had also begun in southern BC in early 1972, but had moved a couple of years later up into the Peace River Region. The others were established from 1973 to 1975, Hilltop being the “new” farm in the area. When I came to live at Graham River, Graham was five years old. I also began to learn of similar community farms in Alaska, across the States, in Latin America, and around the world.

Why community? For three basic reasons. The vision for the communities, and particularly the communities in the wilderness areas came from Brother Sam Fife, a former Baptist preacher from southern Florida. His vision was to see God’s people living together and sharing life together. There is clearly the pattern for such community in the New Testament, a pattern that has been practiced by many moves of the Spirit down through the centuries.

Establishing communities in wilderness places was unique to Brother Sam. Sam Fife believed in the early seventies that there were only a few more years left before a one-world government would be established and liberty would be no more.There were certainly many signs that seemed to agree with that. Brother Sam taught that God’s people needed to establish community farms on the edge of the wilderness where they could support themselves and survive during a time when many Christians would perish.

The third thing that he taught was that during this time of difficulty that was coming, many Christians would be fleeing, looking for a place of refuge. It was Brother Sam’s belief that God would use these communities in the wilderness to prepare a place of refuge for His people. That vision, “to nourish her there,” gripped my heart from the beginning and remains to this day.

The urgency of Sam Fife’s message persuaded around a thousand people to move into community in the Peace River area, as well as a similar number in the States, including Alaska, and a similar number in several Latin American countries, mostly Columbia. In 1972, Brother Sam predicted that we had only about five years left. It was at the end of those five years that I came to Graham River. With hindsight, many years later, we can look back and say, “Boy, he sure got the timing wrong.” Yet, I believe that a large part of the urgency was from the Lord, regardless of the timetables of history.

At the same time, looking at the world today, there is more reason to be pessimistic now about how many years of liberty we have left than it was even then. Yes, many people moved to the communities in the wilderness out of a “herd” instinct, compelled by an external concern. At the same time, many sold all that they had, gave it away, and came to the communities out of obedience to a direct word from God to them personally. And God is always working together with those who love Him to turn all things towards goodness.

For me, for my life, God’s timing was right on time.